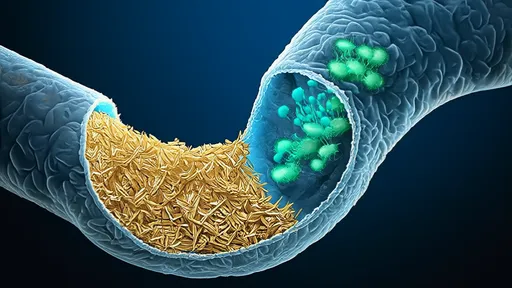

In recent years, the gut-brain axis has emerged as a fascinating and complex communication network linking the enteric nervous system to the central nervous system. This bidirectional pathway involves neural, endocrine, and immune signaling mechanisms, fundamentally influencing brain function and behavior. Among the key players in this intricate dialogue are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), microbial metabolites produced in the gut through the fermentation of dietary fibers. These compounds, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, have garnered significant attention for their potential to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and exert profound effects on neurological health and disease.

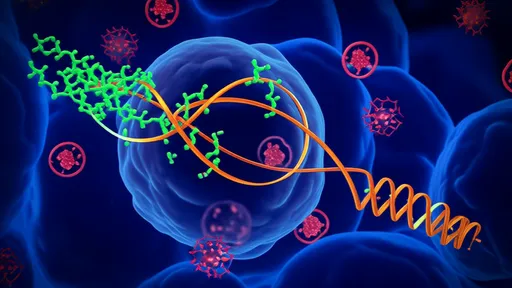

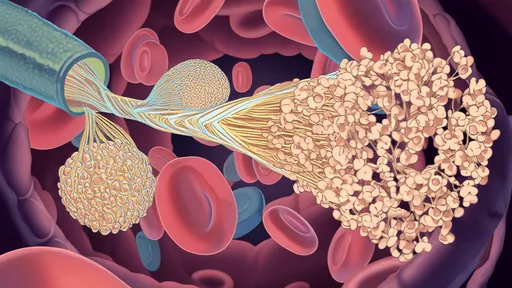

The blood-brain barrier serves as a highly selective interface that protects the brain from harmful substances while allowing essential nutrients to pass through. Composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes, and tight junctions, the BBB maintains the delicate homeostasis required for optimal neural function. For any compound to traverse this barrier, it must either diffuse passively or be actively transported via specific carriers. SCFAs, being small and partially lipid-soluble, possess physicochemical properties that theoretically permit some degree of passive diffusion. However, emerging evidence suggests that their transport is predominantly facilitated by active mechanisms, particularly through monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) expressed on endothelial cells of the BBB.

Monocarboxylate transporters, specifically MCT1 and MCT2, play a pivotal role in shuttling SCFAs from the bloodstream into the brain parenchyma. These transporters are proton-coupled and facilitate the movement of monocarboxylates, including lactate, pyruvate, and SCFAs, across cellular membranes. The expression and activity of MCTs at the BBB can be influenced by various factors, such as diet, gut microbiota composition, and physiological states. For instance, studies have shown that high-fiber diets, which increase SCFA production, can upregulate MCT expression, thereby enhancing the transport of these metabolites into the brain. This adaptive mechanism underscores the dynamic interplay between nutrition, gut microbes, and brain health.

Once inside the brain, SCFAs engage in a multitude of functions that modulate neurological processes. Butyrate, in particular, has been extensively studied for its role as a histone deacetylase inhibitor, which promotes gene expression related to neuroprotection, synaptic plasticity, and anti-inflammatory responses. Acetate and propionate also contribute significantly to brain energy metabolism and immune regulation. Acetate can be utilized as an alternative energy source for astrocytes, while propionate has been shown to influence microglial maturation and function. Collectively, these actions help maintain neuronal integrity, support cognitive functions, and mitigate neuroinflammation.

The implications of SCFA transport across the BBB extend to various neurological and psychiatric disorders. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, characterized by an imbalance in microbial communities, often leads to reduced SCFA production. This deficiency has been linked to the pathogenesis of conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and even depression and anxiety. In animal models, supplementation with SCFAs or interventions that boost their levels—such as prebiotic and probiotic treatments—have demonstrated beneficial effects, including improved memory, reduced amyloid-beta plaque formation, and decreased neuroinflammation. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting SCFA pathways for brain disorders.

Despite the growing body of evidence, several questions remain unanswered. The precise kinetics of SCFA transport across the human BBB, for example, are not fully elucidated. Most studies rely on rodent models or in vitro systems, which may not perfectly recapitulate human physiology. Additionally, the relative contributions of passive diffusion versus active transport require further investigation, as do the potential interactions between different SCFAs and other metabolites during transit. Advanced imaging techniques and biomarker studies in humans are needed to clarify these mechanisms and establish causal relationships between gut-derived SCFAs and brain outcomes.

Moreover, individual variability in gut microbiota composition and MCT expression adds another layer of complexity. Factors such as genetics, age, diet, and lifestyle can all influence how efficiently SCFAs are produced and transported. This variability may explain why some individuals respond more favorably to dietary interventions aimed at modulating the gut-brain axis than others. Personalized approaches, taking into account an individual's unique microbial and metabolic profile, could therefore be key to harnessing the full benefits of SCFAs for brain health.

Looking ahead, research on the gut-brain axis and SCFA transport holds promise for developing novel strategies to prevent and treat neurological diseases. Nutritional interventions, such as high-fiber diets or SCFA supplements, offer a non-invasive and accessible means to support brain function. However, translating these findings into clinical practice requires rigorous human trials to determine optimal dosages, formulations, and long-term safety. Collaborations between neuroscientists, gastroenterologists, and nutritionists will be essential to advance this interdisciplinary field and unlock new avenues for brain health maintenance.

In conclusion, the transport of short-chain fatty acids across the blood-brain barrier represents a critical mechanism within the gut-brain axis, bridging dietary habits, gut microbial activity, and brain physiology. Through active transport via monocarboxylate transporters, SCFAs gain access to the brain, where they exert diverse neuroactive effects. Understanding and leveraging this pathway may pave the way for innovative therapeutic approaches, emphasizing the profound impact of gut health on the mind. As science continues to unravel the complexities of this connection, the adage "you are what you eat" takes on a deeper, more neurological significance.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025