The landscape of vaccine development is undergoing a profound transformation, driven not only by global health demands but also by groundbreaking technological innovations. Among the most promising and unconventional frontiers is the use of plant virus-based vectors, with the Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) emerging as a particularly potent platform for the delivery of vaccine antigens. This approach, which sits at the fascinating intersection of virology, immunology, and molecular farming, represents a paradigm shift from traditional vaccine production methods, offering a unique blend of scalability, safety, and efficacy that could redefine how we combat infectious diseases.

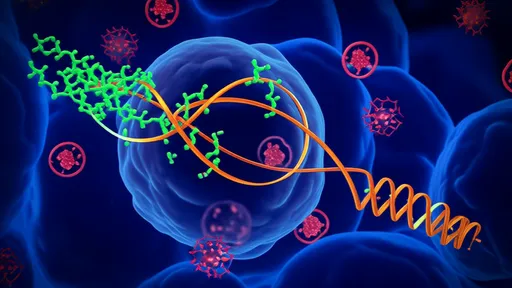

The Tobacco Mosaic Virus, one of the first viruses ever discovered, has been a workhorse in plant biology and virology for over a century. Its simple, rod-shaped structure, composed of a single-stranded RNA genome encapsidated by numerous identical coat protein subunits, provides an elegantly simple and highly modifiable architecture. This simplicity is its greatest strength. Scientists have learned to harness TMV as a viral vector—a vehicle engineered to carry and deliver genetic material into cells. By manipulating its genome, researchers can insert genes that code for specific antigenic proteins from human pathogens. When this recombinant TMV is used to infect host plants, such as Nicotiana benthamiana, the plant’s cellular machinery is hijacked. It dutifully reads the viral instructions and mass-produces not only new viral particles but, crucially, the foreign antigen as well. The result is a biofactory where entire plants become production vessels, generating large quantities of the desired vaccine component.

The advantages of this plant-based production system are multifaceted and compelling. Firstly, it offers an unprecedented level of scalability. Agricultural practices allow for the cultivation of vast quantities of biomass at a relatively low cost. A single acre of tobacco plants can yield kilograms of recombinant protein, a output that dwarfs the capacity of many traditional cell-culture-based bioreactors. This scalability is a critical factor in pandemic preparedness, enabling the rapid production of vaccine doses on a global scale to meet sudden surges in demand. Secondly, the system boasts a superior safety profile. Plant viruses like TMV are incapable of replicating or causing infection in humans. This eliminates the risk of reversion to virulence or contamination with human pathogens—a persistent concern with some live-attenuated viral vaccines or egg-based production systems. The final product is essentially a highly purified plant-derived protein, free from animal-derived components.

From an immunological perspective, the structure of the TMV particle itself acts as a powerful built-in adjuvant. The repetitive, high-density display of the antigen on the surface of the viral capsid is exceptionally effective at stimulating the human immune system. This repetitive pattern is readily recognized by B cells, leading to a robust and potent antibody response even without the need for additional adjuvant chemicals, which can sometimes cause adverse reactions. This phenomenon, known as pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) recognition, triggers innate immune pathways, ensuring the antigen is presented effectively and a strong, lasting adaptive immune response is mounted. This makes TMV vectors particularly effective for generating humoral immunity.

The practical application of this technology has moved decisively from theoretical concept to clinical reality. Numerous research groups and biotech companies have demonstrated its viability against a range of diseases. For instance, vaccines against influenza virus produced in plants using TMV vectors have shown excellent results in clinical trials, eliciting antibody titers comparable to or even exceeding those of licensed flu vaccines. The speed of this platform was starkly highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, where a candidate vaccine based on a related plant virus was developed and entered human trials in a matter of weeks. Beyond infectious diseases, the technology is being explored for cancer immunotherapy. By displaying tumor-specific antigens on the TMV capsid, researchers can "train" the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells, opening new avenues for therapeutic vaccines.

Despite its immense promise, the path to widespread adoption of TMV-vectored vaccines is not without its challenges. A significant hurdle is public perception and regulatory navigation. The concept of a "plant-made" or "virus-derived" vaccine, while scientifically sound, may face skepticism and require extensive public education to gain trust. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA have well-established pathways for approving biologics, but plant-based pharmaceuticals represent a relatively novel category, necessitating clear and tailored guidelines. From a technical standpoint, downstream processing—the purification of the antigen from the complex plant tissue—remains a area for optimization to ensure high purity and yield while controlling costs. Furthermore, ensuring consistent expression levels across different batches of plants, which can be influenced by environmental factors, is crucial for manufacturing consistency.

Looking toward the future, the potential of the TMV platform extends far beyond its current applications. Ongoing research is focused on enhancing the versatility of these vectors. This includes developing chimeric viruses that can display multiple antigens simultaneously, creating multivalent vaccines against several diseases in a single shot. Another exciting frontier is the use of these particles for targeted delivery. By conjugating specific ligands or antibodies to the TMV surface, scientists aim to direct the vaccine directly to specific immune cells or tissues, thereby increasing potency and reducing required dosage. The convergence of TMV technology with other advanced fields, such as nanotechnology and synthetic biology, promises to unlock even more sophisticated and effective vaccine designs.

In conclusion, the utilization of the Tobacco Mosaic Virus as a vector for vaccine antigen delivery is a testament to scientific ingenuity, turning a common plant pathogen into a powerful tool for global health. It challenges conventional paradigms by offering a solution that is simultaneously rapid, scalable, safe, and effective. While hurdles in manufacturing, regulation, and public acceptance remain, the trajectory of this technology is overwhelmingly positive. As research continues to refine and expand its capabilities, plant virus-based vectors like TMV are poised to become a cornerstone of next-generation vaccinology, potentially providing us with the agility needed to confront both existing and future emerging health threats.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025