In the rapidly evolving landscape of nanotechnology, DNA-based systems have emerged as one of the most promising frontiers for molecular computation and nanoscale engineering. A particularly groundbreaking development has been the creation of reconfigurable DNA nanomachines capable of performing computational operations. These tiny yet sophisticated devices leverage the unique properties of DNA—programmability, predictability, and self-assembly—to execute tasks that were once the exclusive domain of electronic computers.

The concept of using DNA for computation is not entirely new. It traces back to Leonard Adleman’s pioneering experiment in 1994, which demonstrated that DNA strands could be used to solve a computational problem. However, the recent focus has shifted toward dynamic, reconfigurable systems that can undergo structural changes in response to specific stimuli, effectively acting as nanoscale robots or machines. These DNA nanomachines are designed to sense inputs, process information, and produce physical or chemical outputs, blurring the lines between computation and actuation at the molecular level.

At the heart of these devices lies the principle of DNA self-assembly. Scientists engineer sequences of DNA that fold into predetermined shapes, such as tiles, tubes, or more complex structures like origami. These constructs serve as the framework upon which computational elements are built. By incorporating functional components—such as aptamers, enzymes, or fluorescent markers—researchers create systems that can detect environmental cues, perform logical operations, and even carry out mechanical tasks.

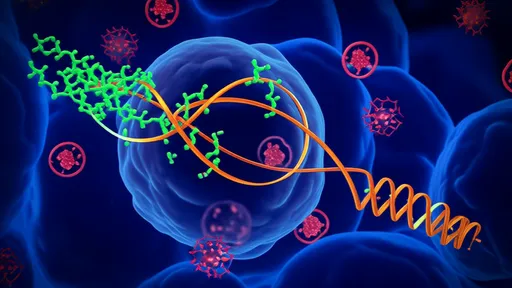

One of the most compelling aspects of reconfigurable DNA nanomachines is their ability to change shape or state in a controllable manner. This reconfiguration is often triggered by specific molecular signals, such as the presence of a particular ion, a short DNA strand, or a protein. For instance, a DNA device might switch from a closed to an open conformation upon binding a target molecule, thereby activating a computational pathway. This behavior is analogous to a transistor switching in an electronic circuit but occurs in an aqueous environment at the nanoscale.

The computational capabilities of these systems are realized through well-designed reaction networks. DNA strand displacement, a process where one DNA strand competitively replaces another in a duplex, is a common mechanism for encoding logical operations. By designing sequences that undergo displacement only under specific conditions, researchers can implement Boolean logic gates, signal amplification circuits, and even complex algorithms. These reactions are highly specific and can be cascaded to perform multi-step computations, much like digital circuits in conventional computers.

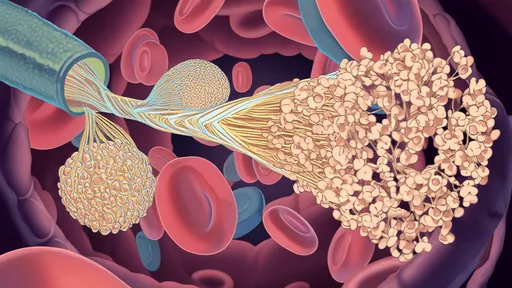

What sets reconfigurable DNA nanomachines apart is their integration of computation with physical action. Unlike traditional software that outputs data on a screen, these systems can produce tangible results. For example, a DNA machine might compute the presence of multiple disease biomarkers and, upon a positive diagnosis, release a therapeutic agent. Alternatively, it could perform a mechanical task, such as transporting a cargo or altering the properties of a material, based on computational decisions made at the molecular level.

Recent advances have demonstrated increasingly sophisticated applications. In one study, a team developed a DNA-based neural network that could recognize patterns of molecular inputs, showcasing the potential for artificial intelligence at the nanoscale. In another, researchers created a DNA robot that could sort molecular cargo on a surface, operating autonomously based on programmed instructions. These examples highlight the versatility and potential impact of DNA nanomachines in fields ranging from medicine to materials science.

However, the development of these systems is not without challenges. One significant hurdle is the issue of robustness. DNA computations are susceptible to errors due to unintended interactions, degradation, or incomplete reactions. Moreover, operating in complex biological environments—such as inside cells—introduces additional variables like nucleases and unpredictable molecular crowding. Researchers are addressing these challenges through error-correction techniques, better encapsulation strategies, and more stable DNA analogs.

Another area of active research is scaling up the complexity of DNA computations. While current systems can handle several inputs and perform multi-step processes, they are still far from matching the complexity of electronic computers. Efforts are underway to create larger and more interconnected networks of DNA devices, potentially leading to molecular systems that can tackle more ambitious problems. Some envision future applications where DNA computers operate inside living organisms, monitoring health and administering treatments in real-time.

The potential medical applications are particularly exciting. Imagine a smart drug delivery system that only releases its payload when it detects a specific combination of cancer markers, thereby minimizing side effects. Or consider diagnostic devices that could continuously monitor blood for pathogens and alert patients or doctors before symptoms appear. These are not distant fantasies but active areas of investigation, with several proof-of-concept studies already published.

Beyond medicine, reconfigurable DNA nanomachines could revolutionize materials science. They could be used to create smart materials that change their properties—such as stiffness, color, or porosity—in response to environmental changes. For instance, a coating that repairs itself when damaged or a fabric that adjusts its insulation based on temperature could be developed using these principles. The ability to compute and respond at the molecular level opens up a new paradigm in material design.

Despite the promise, the path to widespread adoption is long. Current DNA nanomachines often require precisely controlled conditions and can be expensive to produce. Scaling up manufacturing while maintaining reliability is a significant engineering challenge. Furthermore, regulatory hurdles will need to be overcome, especially for medical applications, where safety and efficacy are paramount.

Ethical considerations also come into play, particularly as these technologies approach clinical use. Issues such as privacy (e.g., devices that monitor internal states), autonomy (e.g., systems that make medical decisions without human intervention), and equity (e.g., access to advanced therapies) will need careful discussion. The scientific community is increasingly engaging with these questions to ensure responsible development.

Looking ahead, the convergence of DNA nanotechnology with other fields—such as synthetic biology, robotics, and artificial intelligence—is likely to accelerate progress. Hybrid systems that combine DNA with other materials (e.g., proteins or inorganic nanoparticles) could enhance functionality and stability. Similarly, insights from computer science and engineering are informing the design of more efficient and powerful molecular circuits.

In conclusion, reconfigurable DNA nanomachines represent a thrilling advancement at the intersection of computation and nanotechnology. By harnessing the molecular recognition and self-assembly properties of DNA, scientists are creating devices that not only compute but also act upon their environment. While challenges remain, the potential applications in medicine, materials science, and beyond are profound. As research continues to push the boundaries of what is possible, these tiny machines may one day become integral tools in technology and healthcare, operating silently and smartly at the scale of molecules.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025