In the realm of extremophiles, few organisms capture scientific imagination quite like Deinococcus radiodurans. This seemingly unremarkable bacterium, often found in seemingly innocuous places like dried foods or soil, possesses a almost supernatural ability to survive conditions that would instantly obliterate most other life forms. It can withstand ionizing radiation doses thousands of times greater than what would be lethal to a human, extreme desiccation, oxidative stress, and genotoxic chemicals. Its secret lies not in avoidance, but in an unparalleled mastery of molecular repair, a veritable toolbox of mechanisms dedicated to one task: putting its shattered genome back together with astonishing speed and fidelity.

The sheer scale of the damage D. radiodurans routinely overcomes is difficult to overstate. A radiation dose of 5,000 Gray shatters its genome into hundreds of fragments; for context, a mere 5 Gray is lethal to a human. Where other organisms would succumb to irreversible genetic chaos, this microbe not only survives but often fully recovers within a matter of hours. This resilience is not due to a radiation-proof shield or a radically different genetic code. Instead, its DNA is just as vulnerable as any other. The difference is what happens after the damage occurs. The organism launches a breathtakingly efficient, multi-layered response that scientists are only beginning to fully decipher.

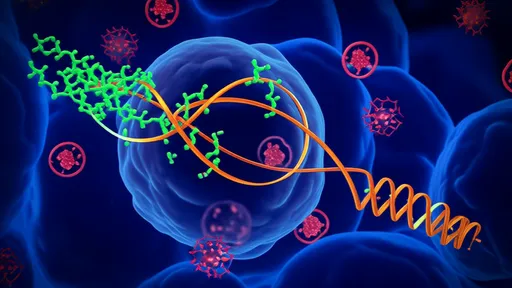

Central to its survival strategy is an extraordinary capacity for DNA damage containment and reconstruction. The initial line of defense involves the swift processing of the fractured DNA ends. Proteins like RecA, a key player in recombination repair found in many bacteria, take on a supercharged role in D. radiodurans. Here, RecA operates with remarkable efficiency, rapidly coating single-stranded DNA and facilitating the homologous pairing necessary to find matching fragments from the cell's multiple genome copies. This process is not a desperate scramble but a highly coordinated effort, suggesting a level of regulation that ensures accuracy even amidst catastrophic damage.

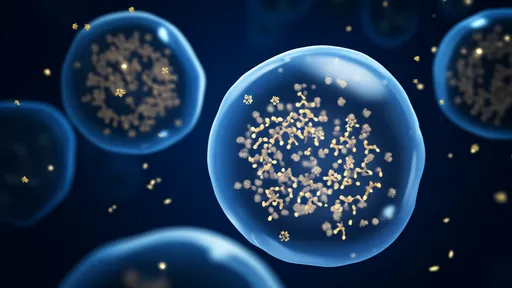

Complementing this is the unique cellular architecture of the bacterium. Its chromosomes are organized in a toroidal, ring-like structure, which some researchers hypothesize helps to physically hold fragments in close proximity after a rupture, preventing them from drifting apart and being lost. This structural organization acts as a pre-emptive first-aid kit, corralling the genetic debris and making the subsequent repair processes vastly more efficient. It’s a elegant example of how physical structure can directly enable biochemical resilience.

Beyond RecA, the organism deploys a specialized arsenal of enzymes dedicated to mending broken DNA. A critical two-step process known as Extended Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing (ESDSA) is a hallmark of its repair toolkit. In the first phase, the broken fragments are used as templates for extensive DNA synthesis, effectively creating thousands of new, overlapping single-stranded segments. These newly synthesized strands then seek out their complementary sequences through homologous recombination, stitching the genome back together from the inside out. This method allows for the accurate reconstruction of the entire genome even from a highly fragmented state, without a single original template remaining intact.

Furthermore, the cell's internal environment is meticulously managed to support these repair operations. D. radiodurans accumulates high concentrations of protective molecules like manganese complexes, which are thought to protect proteins from oxidative damage rather than the DNA itself. This ensures that the repair machinery remains functional even while the cell is under intense oxidative assault from radiation. It's akin to ensuring the firefighters and their equipment are protected from the flames, allowing them to work effectively within the inferno.

The proteome itself is a key component of the toolbox. The suite of DNA repair proteins in D. radiodurans is not entirely unique; many have homologs in other bacteria. The difference lies in their abundance, efficiency, and coordination. Proteins like PprA, a radiation-induced protein that stimulates DNA ligation, and Ddr proteins, which bind to DNA to protect and prepare it for repair, are produced in massive quantities following stress. This represents a strategic investment: the cell dedicates a significant portion of its resources to producing and maintaining a standing army of repair enzymes, ready to be mobilized instantaneously.

This remarkable repair proficiency has profound implications far beyond mere microbiological curiosity. Researchers are actively exploring how to harness these mechanisms for biotechnology and medicine. Understanding how D. radiodurans protects and repairs its proteins could lead to advanced stabilizers for industrial enzymes or pharmaceuticals. More directly, insights into its DNA repair pathways could inform new strategies for radioprotection in humans, potentially benefiting cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy or personnel working in high-radiation environments.

Perhaps the most futuristic application lies in the field of synthetic biology. By isolating and transferring these robust repair mechanisms into more commercially relevant but fragile industrial microbes, scientists aim to create biological factories that are resistant to contamination and can operate under harsh conditions, increasing yield and reducing costs for the production of biofuels, chemicals, and therapeutics.

In essence, Deinococcus radiodurans serves as a living testament to life's incredible tenacity. It challenges our fundamental notions of survival limits. Its DNA repair toolbox is not a single magic bullet but a sophisticated, integrated system of structural organization, protein specialization, and metabolic support. Studying this bacterial champion does more than just satisfy scientific intrigue; it provides a blueprint for resilience, offering nature's best solutions to some of the most extreme challenges imaginable. As research continues to unpack the complexities of its repair mechanisms, we move closer to borrowing a page from its playbook, learning how to better protect and perhaps even rebuild what was once thought to be irreparably broken.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025