In the rapidly evolving landscape of computational technology, a groundbreaking frontier is emerging at the intersection of biology and photonics. Researchers are now harnessing the unique properties of a protein found in ancient microorganisms to build the next generation of computing systems. This protein, bacteriorhodopsin, is not a new synthetic compound engineered in a lab but a biological marvel that has existed for millennia within salt-loving archaea. Its recent application in constructing optical logic gates represents a paradigm shift, moving away from traditional silicon-based electronics towards a future where computation is driven by light and biological components.

The story of bacteriorhodopsin begins not in a computer science department, but in the extreme environments of salt marshes and saline lakes. Here, Halobacterium salinarum, a resilient archaeon, thrives under intense sunlight and high salinity. To survive, it employs bacteriorhodopsin as a photosynthetic protein, using light energy to pump protons across its membrane and generate biochemical energy. This mechanism, a simple yet efficient solar-powered pump, caught the attention of scientists decades ago. Its stability, rapid photocycle, and ability to undergo reversible structural changes under different light wavelengths made it a prime candidate for study far beyond its biological role. Researchers in biophysics and material science began to see its potential not just as a biological curiosity, but as a functional material for technological applications.

Traditional computing, for all its power, is hitting physical limits. The miniaturization of silicon transistors is approaching atomic scales, leading to issues like quantum tunneling and excessive heat generation. Furthermore, the von Neumann architecture, which separates memory and processing, creates a bottleneck known as the von Neumann bottleneck, limiting data transfer speeds. Electrical signals, while fast, are ultimately slower than light and generate significant electromagnetic interference. These challenges have spurred the search for alternative computing paradigms. Optical computing, which uses photons instead of electrons to transmit and process information, promises immense speed, higher bandwidth, and parallel processing capabilities. However, finding materials that can effectively manipulate light for logical operations has been a significant hurdle. This is where the biological world offers an elegant solution.

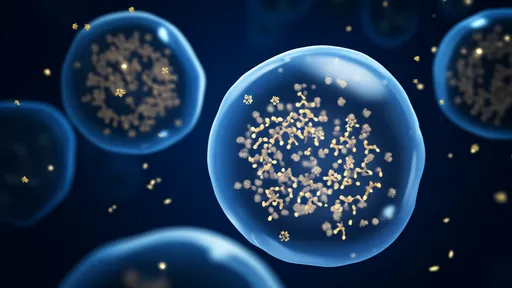

Bacteriorhodopsin's utility in computing stems from its fascinating photochemical properties. When exposed to light, it undergoes a well-defined cycle of structural changes, known as its photocycle. Each intermediate state in this cycle has distinct optical characteristics; it absorbs light of specific colors differently. For instance, the initial resting state (often called the "bR" state) absorbs green light, which triggers its transition to a "K" state. Subsequent intermediates like "M" and "O" absorb blue and red light, respectively. This precise, light-induced switching between states is the fundamental principle that researchers exploit. By using lasers or LEDs of specific wavelengths, they can reliably set the protein to a desired state. More importantly, the state of the protein can be "read" by measuring how it absorbs light, effectively turning it into a optical binary switch—the most basic unit of a logic gate.

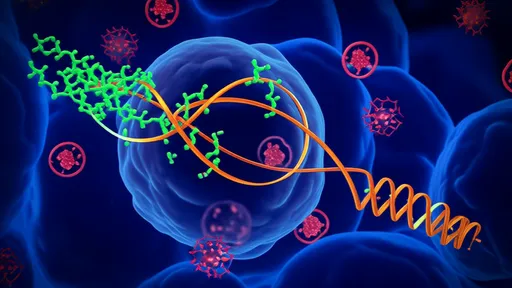

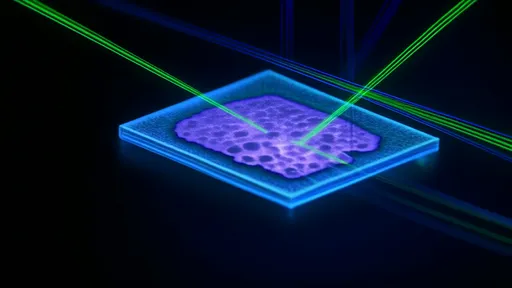

The leap from a light-sensitive protein to a functional logic gate is a feat of interdisciplinary engineering. A logic gate is a fundamental building block of a computer processor; it takes one or more binary inputs and produces a single binary output based on a Boolean logic function (like AND, OR, or NOT). To create an optical logic gate with bacteriorhodopsin, scientists embed the protein within a stable matrix, often a polymer film, creating a thin, bio-based optical component. They then design an experimental setup where the inputs are beams of light of specific wavelengths and intensities. The output is another beam of light, whose properties (e.g., its intensity or wavelength) have been altered by its interaction with the bacteriorhodopsin film. For example, to create an AND gate, the system might be configured so that a high-intensity output beam is only produced if both an input beam A (e.g., green light) AND input beam B (e.g., blue light) are present, switching the protein to a state that allows transmission. The protein’s photocycle acts as the physical mediator of this logic.

The advantages of this bio-photonic approach are profound. First and foremost is the potential for staggering speed. Light-based interactions occur at the femtosecond scale, meaning bacteriorhodopsin-based gates could theoretically operate thousands of times faster than current electronic transistors. Secondly, light does not interfere with itself in the same way electrical currents do, allowing for dense, three-dimensional circuit designs without crosstalk, a significant limitation in modern chip design. Furthermore, these systems operate at very low power levels since the primary energy input is light, and the protein itself is incredibly efficient. Perhaps most intriguingly, this technology offers a path towards massive parallelism. Unlike electronic gates that process signals sequentially, an optical system can process multiple data streams simultaneously using different wavelengths of light in a single channel, a principle known as wavelength-division multiplexing.

Despite its promise, the path from laboratory prototype to commercial technology is fraught with challenges. Integrating a biological component into non-biological computer hardware requires overcoming issues of long-term stability and reproducibility outside of a controlled aqueous environment. While bacteriorhodopsin is robust, ensuring its functionality over years of continuous operation in a computer is a major engineering hurdle. Scaling up from a single logic gate to a complex, interconnected processor comprising millions of gates presents another monumental task. The fabrication techniques for mass-producing uniform, high-quality bacteriorhodopsin films must be developed. Researchers are actively working on solutions, such as engineering more stable mutant varieties of the protein and developing advanced encapsulation polymers to protect it.

The implications of successful bacteriorhodopsin computing extend far beyond simply making faster laptops. This technology is particularly well-suited for specialized applications that demand extreme speed and low power consumption. One promising area is in artificial intelligence and neural networks. The brain itself is a highly parallel, low-power computer, and an optical network built from protein-based gates could be a powerful hardware platform for neuromorphic computing, potentially mimicking neural processes more efficiently than silicon chips. It could also revolutionize fields like image processing, pattern recognition, and cryptography, where processing vast amounts of data in parallel is crucial. Furthermore, as a technology born from biology, it represents a significant step towards greener, more sustainable computing, potentially reducing the immense energy footprint of large data centers.

The exploration of bacteriorhodopsin for optical logic is more than just a technical curiosity; it is a testament to the power of biomimicry. By looking to nature, scientists are finding sophisticated solutions to complex engineering problems that evolution has already refined. This research blurs the lines between the organic and the technological, suggesting a future where our machines are not just inspired by biology but are partially constructed from it. While a full-scale computer running on light and protein may still be on the horizon, the progress made thus far illuminates a vibrant and promising path forward. It challenges our very notion of what a computer can be and what it can be made of, opening a new chapter in the endless quest for computational power.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025