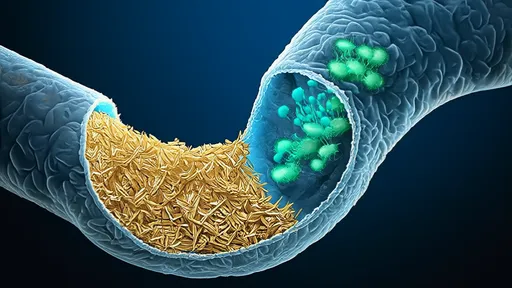

In a groundbreaking development that merges biotechnology with environmental monitoring, scientists have successfully engineered Escherichia coli bacteria to serve as highly sensitive biosensors for detecting environmental toxins. This innovative approach leverages the natural biological mechanisms of these common gut bacteria, reprogramming them to act as early warning systems against hazardous substances in our ecosystems. The implications of this technology extend far beyond laboratory curiosity, offering a practical and scalable solution to the growing challenge of environmental pollution worldwide.

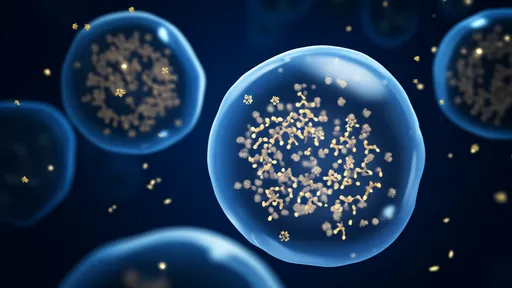

The core concept behind this system lies in the genetic modification of E. coli to produce visible signals—typically fluorescent proteins—when they encounter specific toxic compounds. Researchers have carefully designed genetic circuits that respond to particular environmental contaminants, creating bacterial strains that essentially light up upon detection. This biological detection method represents a significant advancement over traditional chemical analysis techniques, which often require sophisticated equipment and trained personnel. The beauty of these bacterial biosensors lies in their simplicity and potential for widespread deployment in field conditions where conventional monitoring would be impractical or cost-prohibitive.

What makes E. coli particularly suitable for this purpose is its well-understood genetics and rapid reproduction rate. Scientists can precisely manipulate its DNA to create tailored detection systems for various toxins, including heavy metals, pesticides, and industrial pollutants. The bacteria can be engineered to detect multiple contaminants simultaneously, providing comprehensive environmental assessment capabilities. Furthermore, these modified organisms can be deployed in various formats—from freeze-dried kits for field use to integrated systems in water treatment facilities—making them versatile tools for environmental protection agencies and industries alike.

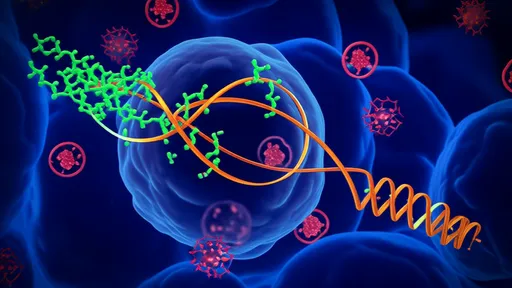

The development process involves sophisticated genetic engineering techniques where researchers insert reporter genes that activate in the presence of target toxins. These genetic constructs typically include a promoter sequence that responds to the specific contaminant, linked to genes that produce easily detectable signals. For instance, when heavy metals like mercury or cadmium bind to the promoter region, it triggers the production of green fluorescent protein, causing the bacteria to glow under specific light conditions. The intensity of this fluorescence can even be correlated with toxin concentration, providing quantitative data about environmental contamination levels.

Field testing of these bacterial biosensors has demonstrated remarkable accuracy in detecting pollutants at concentrations far below levels considered dangerous to human health. In recent trials conducted near industrial areas, the modified E. coli successfully identified heavy metal contamination in water samples with sensitivity matching conventional laboratory equipment. The bacteria detected mercury at concentrations as low as 0.1 parts per billion and lead at 0.5 parts per billion, performance metrics that meet or exceed regulatory standards for environmental monitoring. These results validate the practical utility of biological detection systems for real-world applications.

Beyond mere detection, researchers are developing more advanced systems that can not only identify toxins but also initiate remediation processes. Some engineered strains are being designed to break down certain pollutants upon detection, creating self-contained detection and cleanup systems. For example, scientists have developed E. coli strains that can detect phenolic compounds—common industrial pollutants—and simultaneously produce enzymes that degrade these harmful substances into less toxic compounds. This dual-function approach represents the next frontier in bioremediation technology, potentially revolutionizing how we address environmental contamination.

The implementation of these biosensors faces regulatory considerations and public acceptance challenges. While the modified bacteria are typically rendered unable to survive outside laboratory conditions through additional genetic modifications, concerns about genetically modified organisms in the environment persist. Researchers address these concerns by implementing multiple containment strategies, including nutrient dependency and suicide genes that activate if the bacteria escape controlled environments. Regulatory agencies are working closely with developers to establish frameworks that ensure safe deployment while maximizing the technology's environmental benefits.

Cost-effectiveness represents another significant advantage of bacterial biosensors. Traditional environmental monitoring requires expensive equipment, specialized facilities, and trained technicians, making comprehensive monitoring programs financially challenging, especially for developing regions. In contrast, engineered E. coli systems can be produced at scale relatively inexpensively, with detection kits potentially costing just dollars per test. This accessibility could democratize environmental monitoring, enabling communities worldwide to actively participate in protecting their local environments without relying on centralized testing facilities.

The scalability of this technology allows for applications ranging from individual citizen science projects to large-scale industrial monitoring systems. Homeowners could use simple test kits to check their drinking water, while agricultural operations might deploy sensor networks throughout their properties to monitor pesticide runoff. Municipal water treatment facilities could integrate continuous monitoring systems using immobilized bacteria in flow-through devices. The flexibility of the technology supports adaptation to various contexts and requirements, making it suitable for diverse environmental monitoring needs.

Looking forward, researchers are working to enhance the capabilities of these biological detection systems. Current efforts focus on improving detection limits, expanding the range of detectable toxins, and increasing the stability of the biosensors in various environmental conditions. Some teams are developing bacteria that can detect emerging contaminants like pharmaceutical residues or microplastics, while others are creating systems that can transmit detection data wirelessly to central monitoring stations. These advancements promise to make environmental monitoring more comprehensive, responsive, and integrated with digital technologies.

The development of E. coli-based biosensors represents a remarkable convergence of synthetic biology, environmental science, and engineering. By harnessing the natural capabilities of microorganisms and enhancing them through genetic modification, scientists have created powerful tools for addressing one of humanity's most pressing challenges: environmental pollution. As research progresses and these systems become more refined and widely adopted, they may fundamentally transform how we monitor and protect our natural world, creating a safer and more sustainable future for generations to come.

Ethical considerations remain an important aspect of this technology's development. The scientific community maintains ongoing dialogues about responsible innovation, appropriate safeguards, and equitable access to these monitoring tools. International collaborations ensure that safety standards remain high while promoting knowledge sharing that can benefit all nations facing environmental challenges. This careful, considered approach to development helps ensure that the technology delivers maximum benefit while minimizing potential risks associated with genetically modified organisms in environmental applications.

Practical implementation already shows promising results across various scenarios. From monitoring agricultural runoff in rural communities to detecting industrial pollution in urban areas, these biosensors provide valuable data that informs environmental management decisions. The ability to obtain rapid, on-site results enables timely responses to contamination events, potentially preventing ecological damage and protecting public health. As the technology matures, we can expect to see increasingly sophisticated applications that address complex environmental monitoring challenges across diverse ecosystems and industrial contexts.

The journey from laboratory concept to practical environmental tool demonstrates the power of interdisciplinary innovation. Microbiologists, genetic engineers, environmental scientists, and policy experts have collaborated to create systems that balance technological capability with practical utility and safety considerations. This collaborative approach serves as a model for addressing other complex environmental challenges through scientific innovation. As climate change and pollution continue to threaten ecosystems worldwide, such innovative solutions become increasingly valuable in our collective effort to maintain a habitable planet.

Ultimately, the development of E. coli-based environmental toxin detection systems represents more than just a technical achievement—it embodies a new paradigm in environmental protection. By working with nature rather than against it, and by leveraging the incredible capabilities of even the simplest organisms, we open new possibilities for sustainable coexistence with our environment. As this technology continues to evolve and find new applications, it offers hope for more effective environmental stewardship and demonstrates how scientific creativity can provide practical solutions to global challenges.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025