The vast expanse of the world's oceans conceals a microscopic drama of immense global significance, one where viruses, particularly T4-like bacteriophages, play a starring role in regulating the planet's carbon cycle. For decades, marine science focused on the visible players—phytoplankton, zooplankton, and fish—but the true puppeteers of oceanic processes are only now being fully appreciated. These are not malevolent invaders but essential components of the marine ecosystem, driving biogeochemical processes on a scale that dwarfs human industry.

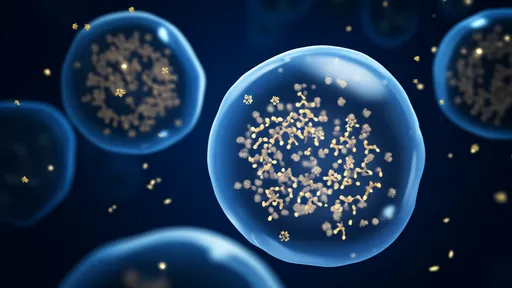

The term "marine virosphere" describes the collective community of viruses in the ocean, a staggering number estimated at 10^30, making them the most abundant biological entities in the marine environment. Within this invisible realm, bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the dominant force. Among them, the T4-like phages, named for their structural and genetic resemblance to the well-studied Enterobacteria phage T4, are ubiquitous. They are not a single species but a vast and diverse group that has evolved to target a wide range of bacterial hosts crucial to marine microbial food webs.

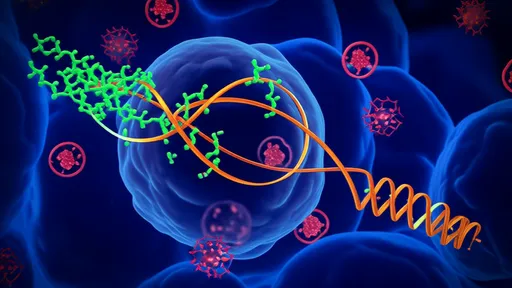

The mechanism by which these phages influence the carbon cycle is both elegant and brutal: the viral shunt. When a T4-like phage infects a bacterial cell, it hijacks the host's machinery to replicate itself, eventually causing the cell to lyse, or burst open. This lysis does two critical things. First, it terminates the bacterial cell's life, preventing the carbon locked within its biomass from moving up the traditional food chain through predation by protozoa and other zooplankton. Second, it releases the cell's contents—including organic carbon and other nutrients—directly back into the dissolved organic matter (DOM) pool of the water column.

This process short-circuits the microbial loop. Instead of carbon being packaged into larger organisms that might eventually sink to the deep ocean, it is kept in the surface waters in a dissolved form, readily available for other bacteria to consume. This creates a rapidly recycling loop of carbon and nutrients within the surface ocean, fundamentally altering the efficiency of carbon export to the depths. The viral shunt, therefore, acts as a counterbalance to the biological carbon pump, the process by which carbon is sequestered in the deep ocean for centuries or millennia.

The sheer scale of this viral activity is breathtaking. It is estimated that phages cause the lysis of approximately 20% of all marine bacterial biomass every single day. This relentless daily turnover releases immense quantities of carbon and is a primary reason the oceans are not significantly more productive than they are. By constantly recycling carbon at the base of the food web, T4-like phages and their viral kin regulate the flow of energy and matter, determining how much carbon is available for sequestration versus how much remains active in surface ecosystems.

Beyond just carbon, the viral shunt also influences other key elemental cycles, such as those for nitrogen and phosphorus. The lysis of bacterial cells releases enzymes and other compounds that can break down complex molecules, making these essential nutrients more bioavailable to the broader microbial community. This nutrient recycling fuels primary production by phytoplankton, which in turn draws down atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis. Thus, the phages indirectly influence the very foundation of the marine food web and the ocean's capacity to act as a carbon sink.

The diversity of T4-like phages is a key factor in their success and impact. Their genetic plasticity allows them to rapidly evolve and adapt to new bacterial hosts, ensuring their persistence despite the arms race with bacterial defense systems like CRISPR-Cas. This constant evolutionary pressure shapes not only the viral populations but also the composition and metabolism of the bacterial communities themselves. By selectively lysing certain bacterial strains, phages can determine which species thrive and which diminish, effectively curating the microbial cast that performs the biochemical reactions driving the carbon cycle.

Understanding the role of T4-like phages is no longer a niche academic pursuit; it is critical for refining global climate models. Current models often poorly represent the complex interactions within the microbial loop and largely ignore the regulatory function of viruses. Incorporating the viral shunt into these models could dramatically improve predictions of how the ocean will respond to climate change, including warming, acidification, and shifts in nutrient availability. A warmer ocean will undoubtedly alter viral infection rates and host-phage dynamics, with cascading consequences for carbon cycling that we are only beginning to foresee.

Research in this field relies on cutting-edge techniques like metagenomics, which allows scientists to sequence and analyze the collective genetic material scooped from seawater samples. This has revealed the incredible genetic diversity of T4-like phages and their prevalence across all oceanic basins, from the sunlit tropics to the frigid polar seas. However, the challenge remains moving from genetic identification to understanding actual function—determining which viruses infect which hosts under real-world conditions and quantifying the precise rate of carbon flow through the viral shunt.

In conclusion, the story of T4-like bacteriophages is a powerful testament to the interconnectedness of life on Earth. These microscopic entities, once overlooked, are now recognized as master regulators of the ocean's biogeochemical engine. Through the relentless and pervasive process of the viral shunt, they dictate the fate of carbon on a planetary scale, balancing the flow between the atmosphere and the deep ocean. As we grapple with the challenges of climate change, acknowledging and integrating the role of this viral world is not just an academic exercise—it is essential for understanding the past, present, and future of our planet's climate.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025