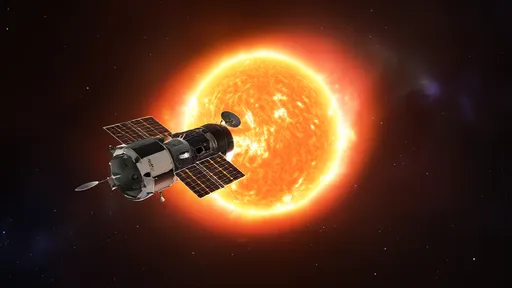

The sun has always captivated humanity, but its polar regions have remained one of our star's most profound mysteries. For centuries, astronomers could only observe the sun from the ecliptic plane, the flat disc of space where planets orbit, leaving the poles virtually unseen and poorly understood. That is, until now. The Solar Orbiter, a collaborative mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA, has done what was once thought impossible: it has beamed back the first-ever close-up images and data from the sun's polar regions, fundamentally altering our comprehension of solar activity and its influence on the solar system.

Launched in February 2020, the Solar Orbiter was engineered for a specific and daring purpose: to tilt its orbit out of the ecliptic plane and gain a vantage point never before achieved by a solar observatory. This maneuver required a series of complex gravitational assists from Venus and Earth, a delicate celestial dance that has now placed the spacecraft in a unique orbit, allowing it to gaze directly upon the sun's poles. The data now streaming back to Earth is not merely incremental; it is revolutionary, offering a全新的视角 (a completely new perspective) on the dynamics that govern our star.

The initial images have stunned the scientific community. They reveal a stunning and unexpected landscape at the polar regions. Unlike the familiar sunspot-dotted surface we see from Earth, the poles are dominated by vast, intricate structures of coronal holes. These are regions where the sun's magnetic field opens out into space, allowing solar wind to stream away at tremendous speeds. The clarity and detail of these structures are unprecedented. We can see feathery, filament-like patterns stretching across the polar caps, suggesting a complex and highly dynamic magnetic environment that is far more turbulent and structured than previous models predicted.

One of the most significant breakthroughs concerns the origin of the solar wind. For decades, scientists have known that the fast solar wind, which can travel at over 500 miles per second, originates from coronal holes. However, the precise mechanisms accelerating this wind have been a subject of intense debate. The Solar Orbiter's instruments, particularly its Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) and its Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), have captured tiny, fleeting magnetic explosions at the boundaries of these polar coronal holes. These "nanoflares" or "jetlets" appear to be continuously pumping energy into the corona, acting as miniature accelerators for the solar wind particles. This data provides the most compelling evidence yet that these pervasive, small-scale magnetic reconnections are a primary driver of the fast solar wind, solving a puzzle that has persisted for over half a century.

Furthermore, the mission is shedding new light on the sun's magnetic field itself. The sun's global magnetic field, which flips polarity every 11 years, is believed to be generated by a dynamo process deep within its interior. The poles are crucial to this process, acting as a graveyard for magnetic fields from decaying sunspots at the end of each solar cycle. How these fields are transported, recycled, and amplified at the poles is central to understanding the solar cycle. Solar Orbiter's measurements indicate that the flow of plasma at the poles, known as the meridional flow, is faster and more structured than models assumed. This suggests a far more efficient mechanism for transporting magnetic flux to the poles, which could dramatically improve our ability to forecast the strength and timing of future solar cycles. Accurate predictions are vital, as a powerful solar maximum can threaten satellites, power grids, and astronauts.

The implications of this research extend far beyond academic curiosity. Space weather, driven by solar activity like coronal mass ejections and solar wind, can have catastrophic effects on modern technology. A severe solar storm could potentially knock out global power grids and communication networks for weeks or months. By understanding the source of the solar wind at the poles and the dynamics of the polar magnetic field, scientists can develop significantly more accurate models to predict when such damaging eruptions might occur. The Solar Orbiter's data is providing the foundational knowledge needed to transform space weather forecasting from a rudimentary art into a precise science, ultimately helping to protect our technologically dependent civilization.

This is only the beginning. The Solar Orbiter's mission is far from over. In the coming years, it will continue to use Venus's gravity to increase the inclination of its orbit, eventually reaching angles of up to 33 degrees, providing even more direct views of the poles. Each new pass will yield higher-resolution data and likely reveal more surprises. The mission represents a triumph of international collaboration and engineering ingenuity, a testament to humanity's relentless pursuit of knowledge. It peels back another layer of the sun's mysteries, reminding us that even our own star, a constant presence in our sky, still holds profound secrets waiting to be discovered. The data from the solar poles is not just a collection of numbers and images; it is a new chapter in solar physics, one that promises to rewrite textbooks and redefine our relationship with the star that gives us life.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025