In a landmark study that could reshape our understanding of neurodegenerative disorders, researchers have unveiled compelling evidence about how tau proteins propagate through the brain. This mechanism, long suspected but poorly understood, appears to play a central role in the progression of conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and certain forms of dementia. The findings not only clarify a key pathological process but also open promising new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

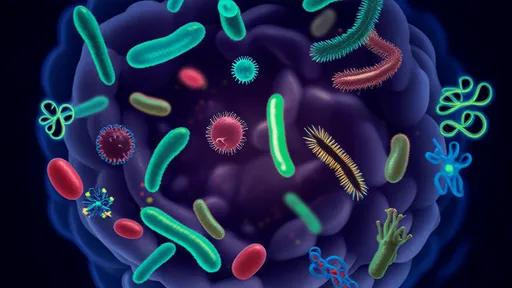

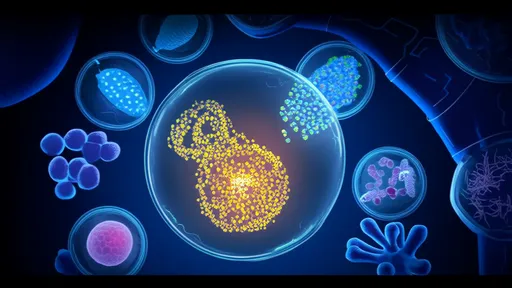

For decades, scientists have observed that the spread of misfolded tau protein correlates strongly with cognitive decline and neuronal loss. Tau, which normally stabilizes microtubules in healthy neurons, can become hyperphosphorylated and form toxic aggregates known as neurofibrillary tangles. These tangles disrupt cellular function and are a hallmark of several neurodegenerative diseases. What remained elusive was precisely how these pathological tau species move from one brain region to another, seeding dysfunction in previously healthy tissue.

The new research, spearheaded by teams across multiple institutions, demonstrates that tau propagation occurs via a prion-like mechanism. In this context, misfolded tau acts as a template, inducing normally folded tau in neighboring cells to also misfold and aggregate. This cascade effect allows the pathology to spread neural network by neural network, effectively turning the brain’s connectivity into a pathway for its own deterioration. The study utilized advanced imaging, neuronal tracing, and biofluid biomarkers to track this process in both animal models and human post-mortem tissue with unprecedented resolution.

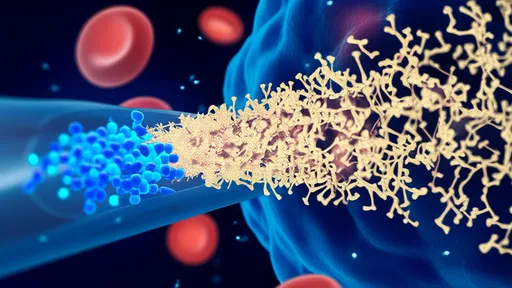

One of the most striking aspects of the discovery is the role of synaptic connections. The researchers found that tau proteins are preferentially released at synapses and taken up by connected neurons. This trans-synaptic transfer means that the brain’s functional architecture—the very circuits that underlie memory, emotion, and thought—becomes the conduit for disease progression. It explains why neurodegenerative diseases often follow predictable patterns of spread, mirroring the brain’s intrinsic wiring diagrams.

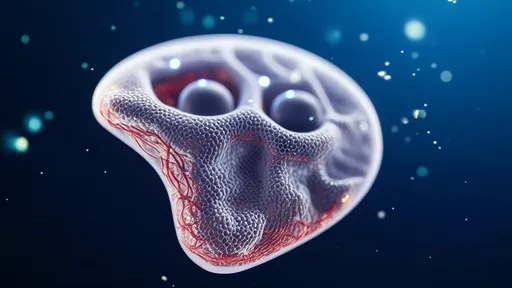

Another critical insight involves extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes. These tiny membrane-bound packets are released by cells and can carry proteins, lipids, and RNA between neurons. The study provides strong evidence that pathological tau is secreted within exosomes, which then ferry the toxic cargo to other cells. When these vesicles are ingested by healthy neurons, they introduce misfolded tau that can nucleate further aggregation. Blocking this exosomal pathway, as the researchers showed in experimental models, significantly slows disease progression.

The implications for diagnosis are profound. If tau propagation can be tracked—perhaps through novel PET ligands or sensitive blood tests—it might be possible to stage neurodegenerative diseases much earlier and with greater accuracy. Researchers are already exploring biomarkers that reflect synaptic release of tau or the presence of tau-bearing exosomes. Such tools could enable clinicians to monitor disease activity and response to treatment in real time, moving beyond static anatomical assessments to dynamic, biological tracking.

On the therapeutic front, the findings suggest multiple strategies to halt or slow disease. Interventions could aim to prevent the release of tau from affected neurons, block its uptake by healthy ones, or clear extracellular tau before it spreads. Antibodies that target specific forms of pathological tau are in development, and some have shown promise in early clinical trials. Similarly, small molecules that stabilize normal tau conformation or enhance cellular clearance mechanisms represent another attractive approach.

Yet challenges remain. The brain is exquisitely complex, and interfering with intercellular communication carries risks. For instance, disrupting exosomal function might impede normal cellular maintenance or signaling. Moreover, tau pathology doesn’t operate in isolation; it interacts with other disease factors like amyloid-beta, inflammation, and vascular damage. Successful treatments will likely require combination therapies that address multiple aspects of the disease process.

Ethical and philosophical questions also emerge from this research. If we can predict the spread of degeneration through someone’s brain based on its connectivity, what does that mean for personal identity and autonomy? The very structures that make us who we are—our memories, personalities, and capacities—are both the target and the transport route of the disease. This dual role underscores the profound intimacy of neurological illness, where the organ of the self is turned against itself.

Looking ahead, the field is poised to build on these discoveries. Future research will need to clarify the precise molecular signals that trigger tau release and uptake, identify genetic and environmental modifiers of spread, and validate therapeutic candidates in diverse populations. Longitudinal studies in humans, coupled with sophisticated model systems, will be essential to translate these mechanistic insights into clinical benefits.

In summary, the elucidation of tau propagation represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience. It moves us from a static view of neuropathology to a dynamic one, in which disease is a process that travels and evolves. This not only deepens our comprehension of how neurodegeneration unfolds but also illuminates new possibilities for stopping it in its tracks. For millions affected by these devastating conditions, that hope is invaluable.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025