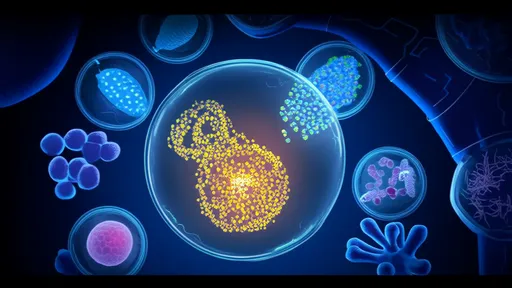

The realm of materials science is witnessing a paradigm shift with the emergence of self-healing materials, a class of substances that possess the intrinsic ability to autonomously repair damage, much like biological organisms. Drawing profound inspiration from nature's own repair mechanisms—be it the clotting of blood in animals or the wound healing in plants—scientists and engineers are pioneering a new generation of materials that promise to revolutionize durability, safety, and sustainability across countless industries. This is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental reimagining of what materials can do, moving from passive, degradable entities to active, resilient systems that can recover from wear, tear, and catastrophic failure.

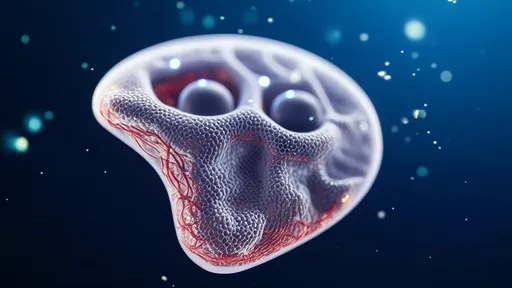

The foundational principle behind these ingenious materials lies in mimicking biological processes. In living systems, damage triggers a complex, often multi-stage response. For instance, when human skin is cut, platelets rush to the site to form a clot, followed by inflammation, tissue regeneration, and finally remodeling. Researchers have sought to replicate this autonomic response in synthetic materials through various ingenious strategies. The most prominent approaches can be broadly categorized into two families: those that rely on embedded healing agents and those that utilize reversible chemistry.

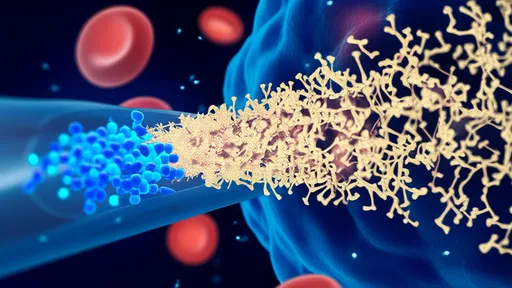

One of the earliest and most commercially explored strategies involves vascular and capsule-based systems. Inspired by the human circulatory system which delivers healing components to a wound, vascular self-healing materials contain a network of microscopic channels or tubes filled with a liquid healing agent. When a crack propagates through the material, it ruptures these vessels, allowing the healing agent to wick into the damaged area. Upon contact with a catalyst also embedded within the material, the agent polymerizes, effectively gluing the crack shut and restoring structural integrity. Similarly, capsule-based systems disperse countless microcapsules throughout the material matrix. Damage breaks these tiny capsules, releasing their healing payload. While effective, a limitation of this approach is its finite healing capacity; once the reservoirs or capsules in a specific area are depleted, that region can no longer repair itself.

A more recent and promising avenue of research focuses on intrinsic self-healing, where the material itself is designed with a latent ability to heal without the need for sequestered healing agents. This is achieved through sophisticated reversible chemical bonds. These are molecular interactions that can break under stress but have the innate ability to reform under specific conditions, such as the application of heat, light, or simply the passage of time. Examples include materials incorporating Diels-Alder reactions, hydrogen bonding, ionomeric arrangements, or dynamic disulfide bonds. When a crack forms, these reversible bonds break, but given the right stimulus—often something as simple as moderate heat—the bonds reassemble, zipping the material back together. This method offers the tantalizing prospect of near-limitless healing cycles, as the healing capability is an inherent property of the entire material bulk, not a finite embedded resource.

The applications for these bio-inspired materials are vast and transformative. In the aerospace and automotive industries, the integration of self-healing polymers and composites could lead to components that automatically seal micro-cracks caused by vibration and fatigue, drastically improving safety and extending the lifespan of aircraft fuselages, wind turbine blades, and car body panels. This reduces the need for frequent inspections and costly preventative maintenance, heralding a new era of reliability.

The electronics sector stands to benefit enormously. The development of self-healing circuits and batteries could solve critical failure points. Imagine a smartphone battery that can repair dendrite formation or a flexible display that can heal scratches and minor cracks, thereby significantly enhancing product longevity and reducing electronic waste. Researchers are already making strides with conductive polymers and gels that can restore electrical pathways after being severed.

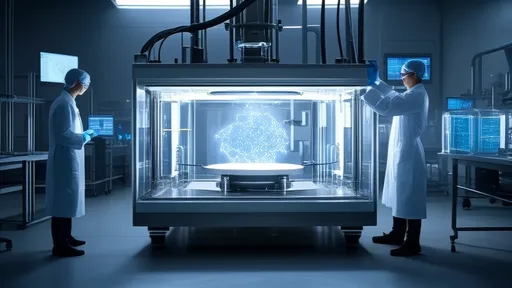

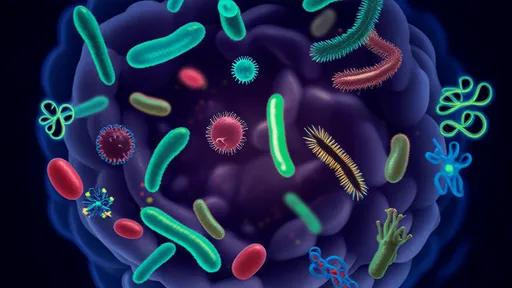

Perhaps one of the most impactful applications is in civil engineering and infrastructure. Self-healing concrete is poised to change the face of our cities. By embedding bacteria that produce limestone or capsules containing healing agents into concrete, cracks can be automatically sealed before they expand and compromise the structural integrity of bridges, buildings, and roads. This not only enhances safety but also offers monumental economic and environmental benefits by reducing the massive carbon footprint associated with constant concrete production and repair works.

Furthermore, the field of soft robotics and biomedicine is ripe for disruption. Self-healing hydrogels and elastomers are ideal for creating soft robots that can operate in unpredictable environments and withstand punctures or cuts. In medicine, these materials could lead to longer-lasting and safer implants, drug-delivery devices that can repair themselves, and even advanced wound dressings that actively participate in the healing process of the body itself.

Despite the exhilarating progress, significant challenges remain on the path to widespread commercialization. A primary hurdle is the scalability of production. Creating intricate microvascular networks or uniformly dispersing millions of microcapsules on an industrial scale is a complex and costly endeavor. For intrinsically healing materials, synthesizing polymers with the precise reversible chemistry required often involves expensive precursors and multi-step processes. Engineers are tirelessly working to develop more economical and scalable manufacturing techniques to bring these materials to market.

Another critical challenge is optimizing the healing performance under real-world conditions. Many self-healing mechanisms require specific triggers, such as heat, UV light, or a lack of oxygen, which may not always be present at the damage site. The speed of healing is also a factor; while some materials heal in seconds, others require hours or days, which may not be practical for certain applications. The ultimate goal is to develop materials that can heal quickly, completely, and autonomously in ambient conditions, much like biological systems do.

Looking ahead, the future of self-healing materials is incredibly bright and points toward increasingly complex and intelligent systems. The next frontier involves moving beyond simple crack repair to multi-functional self-healing. Researchers are exploring materials that can not only restore mechanical strength but also electrical conductivity, optical clarity, or even antibacterial properties simultaneously. The integration of sensing capabilities is another exciting direction, creating materials that can not only heal but also report on the location and extent of the damage, providing a smart, responsive system that mirrors the sensory feedback loops found in biology.

The exploration of self-healing materials, fueled by the elegant principles of biomimicry, is more than a technical pursuit; it is a step towards a more sustainable and resilient future. By bestowing upon inanimate objects the gift of healing, we are fundamentally altering our relationship with the manufactured world, promising a future where products last longer, waste is diminished, and safety is inherently built-in. This journey, from observing a wound close to designing a concrete that seals its own cracks, stands as a powerful testament to human ingenuity and our enduring inspiration from the natural world.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025