For over a decade, marine biologists have maintained a silent vigil beneath the waves, tracking a subtle yet profound shift in the world’s oceans. The subject of their watch is not a charismatic megafauna or a vanishing coral reef, but something far more fundamental: the changing chemistry of seawater itself. This phenomenon, known as ocean acidification, represents one of the most significant and understated consequences of rising atmospheric carbon dioxide. As CO2 dissolves into the sea, it triggers a cascade of chemical reactions, lowering the pH and altering the very building blocks of marine life. The long-term observation of how ecosystems respond to this creeping change is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical endeavor to understand the future of our planet’s largest habitat.

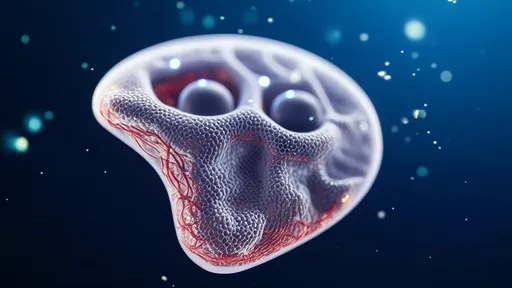

The journey of a carbon dioxide molecule from the atmosphere into the depths of the ocean begins at the air-sea interface. Here, a constant exchange occurs, a delicate dance that has maintained a stable equilibrium for millennia. However, the immense volume of CO2 released by human activities since the Industrial Revolution has overwhelmed this natural balance. The ocean, in its immense capacity for absorption, has taken up nearly a third of anthropogenic carbon emissions. This service comes at a cost. When CO2 dissolves, it forms carbonic acid, which subsequently dissociates, releasing hydrogen ions and carbonate ions. The increase in hydrogen ions is what defines acidity, leading to a measured drop in pH. More critically, this reaction reduces the availability of carbonate ions, which are essential for countless marine organisms to build their shells and skeletons.

To comprehend the long-term trajectory of acidification, scientists rely on a network of sustained observational programs. Stations like the Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT) and the European Station for Time series in the Ocean (ESTOC) have collected painstakingly precise measurements for decades. Moored sensors and repeated research cruises provide a continuous stream of data on pH, dissolved inorganic carbon, total alkalinity, and carbonate mineral saturation states. This data paints an unambiguous picture: the ocean is growing more acidic at a rate unparalleled in the geological recent past. The trend is global, but it is not uniform. The Arctic and upwelling systems along the western coasts of continents are experiencing these changes most acutely, their cold, nutrient-rich waters absorbing CO2 more readily. These time series are the bedrock upon which our understanding is built, offering irrefutable evidence of the physical and chemical transformation underway.

Perhaps the most immediate and visible ecosystem responses are observed in the calcifying organisms that rely directly on carbonate ions. Coral reefs, the vibrant metropolises of the sea, face a dual threat from warming waters and acidification. Long-term monitoring of reefs, such as those on the Great Barrier Reef and in Kane'ohe Bay, Hawaii, reveals a troubling decline in calcification rates. Corals struggle to deposit their calcium carbonate skeletons, leading to weaker frameworks that are more susceptible to storm damage and bioerosion. The very architecture of the reef begins to crumble, jeopardizing the immense biodiversity it supports. Similarly, shellfish like oysters, mussels, and clams face developmental hurdles. Hatcheries along the North American Pacific coast have already documented massive larval mortality events directly linked to periods of intense acidification caused by seasonal upwelling. The shells of open-sea pteropods, tiny swimming snails that are a fundamental food source for salmon and whales, have been observed dissolving in the more corrosive waters of the Southern Ocean.

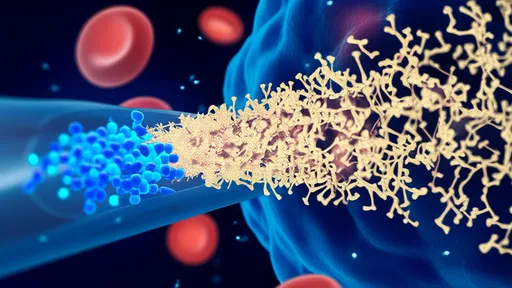

Beyond the calcifiers, the ramifications ripple through entire food webs in ways that are only beginning to be understood through sustained ecological study. The base of the marine food chain, phytoplankton, exhibits a complex and varied response. Some species, particularly certain types of cyanobacteria, may thrive in a high-CO2 world. However, for diatoms—a crucial group encased in silica shells—the picture is less clear. Changes in phytoplankton community structure could fundamentally alter the efficiency of the biological pump, the process that transports carbon from the surface to the deep ocean. For the zooplankton that graze on them, and the fish that in turn prey on them, acidification can impair growth, reproduction, and most notably, neurological function. Studies tracking fish populations over generations show that elevated CO2 can interfere with neurotransmitter function, leading to altered behavior, such as a loss of predator avoidance instincts and homing abilities.

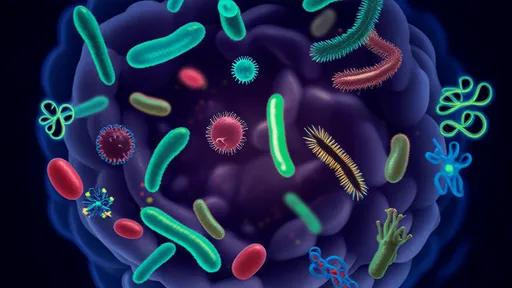

The response of ecosystems is not monolithic; it is a tapestry woven with threads of resistance, resilience, and adaptation. Long-term observations are crucial for identifying refugia—areas where conditions change more slowly or where local factors like seagrass photosynthesis mitigate acidity. They also document the potential for evolutionary adaptation. Some populations of sea urchins and coccolithophores have shown a capacity to adjust their physiological processes over multiple generations when exposed to gradually increasing CO2. However, the relentless pace of anthropogenic acidification threatens to outstrip the innate adaptive capacity of many species. The real-world outcome is not a simple swap of one species for another, but a potential simplification of entire ecosystems, a loss of functional diversity, and a reduction in their overall productivity and stability.

This vast undertaking in long-term observation faces significant challenges. Maintaining funding for decadal-scale projects is a perpetual struggle. The marine environment is a harsh master, and technology—from sensor drift to mooring failures—can and does falter. Perhaps the greatest scientific challenge is attribution. The ocean is a complex system where acidification does not act in isolation; it is concurrent with warming, deoxygenation, pollution, and overfishing. Disentangling the specific effects of acidification from this cocktail of stressors requires sophisticated multidisciplinary approaches and models grounded in robust, long-term data. Despite these hurdles, the scientific community has built an unprecedented global coalition, from remote sensing to in situ sensors to citizen science initiatives, all aimed at keeping a finger on the pulse of the changing ocean.

The uninterrupted time series of data now stretching back thirty years delivers a message that is both stark and unequivocal. Ocean acidification is not a future threat; it is a present-day reality with measurable consequences. The observed shifts in ecosystem structure and function are early warnings of a system under duress. The continued acidification locked in by current CO2 levels guarantees that these pressures will intensify for centuries to come. The long-term observations provide the essential foundation for policy decisions, guiding the development of strategies for carbon mitigation, the management of vulnerable fisheries, and the design of marine protected areas. They tell the story of an ocean changing at a rate unseen for millions of years, and they offer the only hope we have of understanding—and potentially mitigating—the fate of the blue heart of our planet.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025